Unique Aspects Of Social Media In Japan

Like all modern societies Japan is taking the leap towards artificial intelligence (AI), utilising its advantages of connection to the full. Social media as well as robotics have become an adjunct to modern

living with both positive and negative repercussions. The Japanese are in themselves individual islands that float together in a sea of harmony. They have maintained enormous self-restraint in terms of emotions and often share

very little of themselves with others. The advent of social media has created opportunities for far greater online connection, but this is often only superficial, and it appears loneliness is on the increase among its population.

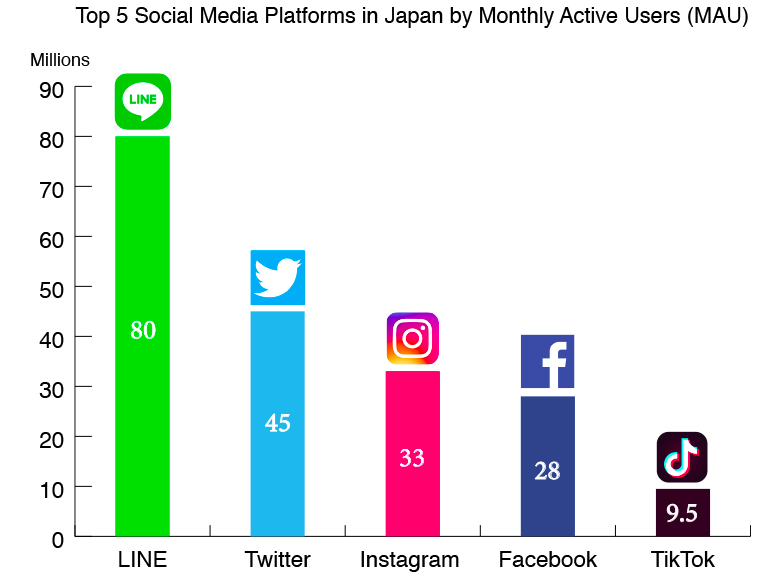

The Japan based app LINE is the most popular and successful for messaging and is similar to WhatsApp, Messenger or WeChat. LINE active users are estimated at 81 million or approximately 60 per cent of the

entire Japanese population. In line with the need by the Japanese for privacy LINE has a lack of posting, an activity that we are used to on Twitter and Facebook.

Although Facebook is the global leader, in Japan its only fifth on the ladder with 26 million active users. Its prime users are now in the older age bracket, a trend noticeable since 2016. In 2019 Facebook

lost significant ground as younger users, especially females, shifted to Instagram. Facebook is also used for business networking (aside from LinkedIn).

Twitter’s success in Japan is interesting. Many Japanese reply on Twitter to get weather alerts, traffic updates, train timetable changes and emergency service broadcasts. Twitter Japan’s success is based

on the easy use of the Kanji language on the platform, since each Kanji character carries more meaning and therefore far more can be said in the maximum 280-full-width characters. This is one of the reasons for its success

in Japan, the other being the lack of personal information that users need to expose on this platform.

In Japan, people see LinkedIn as an employment search platform; the idea of being seen by their employer as looking for a job is unprofessional and in some sense, disrespectful from a cultural standpoint.

Japan is generally a face-to-face driven culture where reputation precedes individualisation.

A strict set of cultural forms have set the basis for encouraging creativity and individuality as long as it goes through a certain set of rules first. As a result, the idea of having an individual

voice online can be relatively limited for those looking to maintain a specific reputation for persona. It is no wonder that LinkedIn faces difficulties in penetrating the wider Japanese market.

Eight, a Japanese social media app that allows you to digitally manage your business cards, is worth mentioning here as it was able to reach 1 million users in just three years. Sites such as Eight have found

success by integrating social media with Japanese culture.

Personal space and privacy dictate the use of social media platforms far more than in any other country. The repressive effects of Japan’s ancient feudal system and more recently the military policing during

the 1930’s and World War II created a stigma for sharing personal information, including views and opinions. This is true for sharing within small groups so there is even more reticence when it comes to exposing oneself on

the internet. Selfies and photos of a personal nature are far less prevalent than in the west, and general imagery of external objects, places and activities dominate for all demographics. Images of pets, inanimate objects,

or even favourite anime characters are preferred as profile pictures rather than an image of the user.

In Japan sharing views and opinions is often only done with careful consideration and it is common for people to ask for permission to share any content or information taken from another person’s social media

account. Fewer Japanese than in the west post on their own accounts, however they often “like” or react to others’ posts. This lack of personal promotion is surely based on the hegemony of the whole society over the individual.

© Kiyoshi Matsumoto, 2022, Sydney, All Rights Reserved

No responses yet